Two out of three of the artists have gone for experiments in fermentation – but it’s Laleh Khorramian’s kaleidoscopic prints that are really mouthwatering.

Pickling isn’t usually seen as an art form. But two out of the three artists in the Vasseur Baltic artists’ award have been fermenting: Ima-Abasi Okon to explore the probiotic benefits of fermentation and Fernando García-Dory to showcase the pickling skills of a local community interest company. Okon’s dehydrated, vacuum-packed pile of oxtail stew with scotch bonnet, ashwagandha, lion’s mane and tulsi is piled up on a cane chair, while jars of produce from The Pickle Palace line the wooden structures of García-Dory’s installation.

Presumably, pickling hasn’t been high on artists’ agendas because visually it doesn’t pack much of a punch. Certainly, Okon’s seated stack is an intriguing, juicy, visceral lump of flesh and guts, but García-Dory’s jars are reminiscent of a weekend meander around Sainsbury’s. The Vasseur Baltic artists’ award – a biennial award of £25,000 (plus £5,000 artist fee) offered to three emerging artists, judged by three other artists – is bursting at the seams with ideas. Wonderful, provocative ideas that question how culture and nature intersect, how land can unite communities, how life can be preserved. It is interesting, but it is not arresting.

However, interesting is still an important word when viewing art. García-Dory does an outstanding job of introducing us to a Lake District farm that has searched for ways to diversify and educate; a sailing university of interdisciplinary arts that challenged the usual urban sites of artistic production; and the Freemen that are protecting the Town Moor, an area of greenery in the centre of Newcastle upon Tyne.

In 2009, García-Dory established Inland, a collective dedicated to agricultural, social and cultural production where exhibition creation is as important as cheesemaking. Consequently, the artist’s presentation is a museum of organisations that use making to interact with the natural world and build community. The shelves hold bars of soap from a north England farm, knitted lampshades from a local creative and botanical illustrations by the naturalist John Hancock. Alongside, there are photographs of sheep grazing in the centre of Madrid, a bus that doubles up as an art gallery and Federico García Lorca’s mobile theatre. Despite this, I still can’t shake the feeling of being in a trendy minimalist shop.

In contrast, Okon has a big, empty space. Empty but for the artist’s certificates in food hygiene, manual handling and food allergy awareness, the music licence for her sound piece, and boneshaking bass emanating from a Leslie speaker in the following room. The documentation allows the artist to serve the aforementioned oxtail as food and to play a screwed audio track.

Drawn in by the up-tempo beats, we walk into Okon’s second space, where the cane swivel chair stacked with oxtail faces the speaker made in decorative hardwoods. There are traces of invisible people everywhere: the certificates of labour in the first empty room, the chair as if someone has suddenly stepped outside, the title cards that read like silent transcripts. Okon had been researching palliative care methods and the ghostly figures get me thinking about my own fleshy cocoon and its fermentation capabilities once I too disappear.

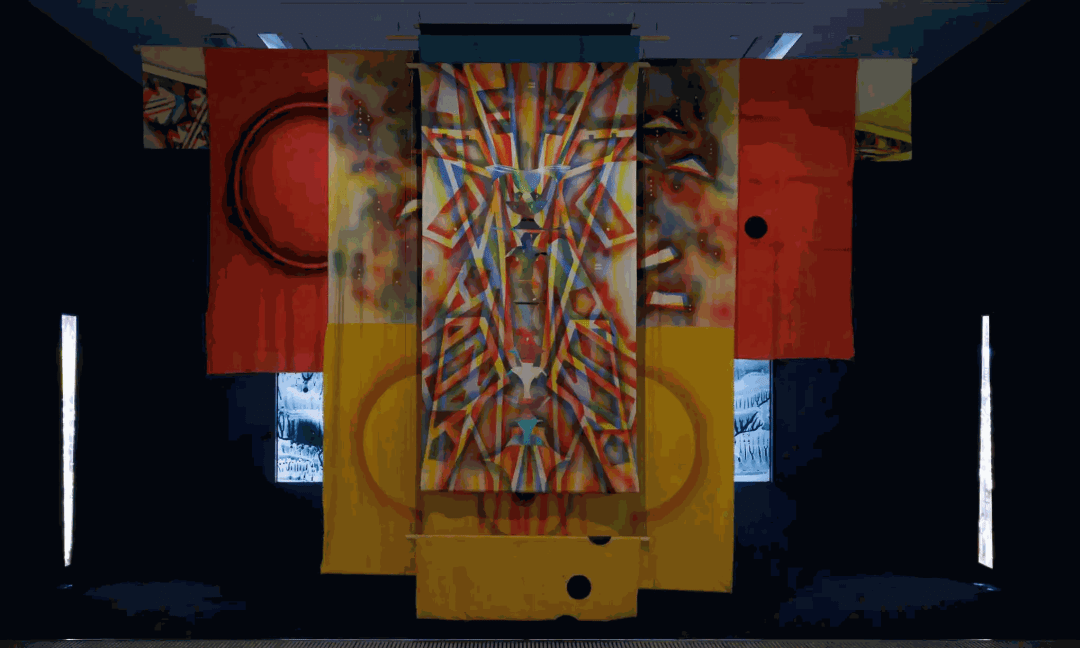

Sometimes though, I want to be run over by an artwork, knocked on the head so hard my eyes are wide and my brain is silent, which is exactly what happens in the presence of Laleh Khorramian’s work in the final space. Huge swathes of fabric rise up, layered in prints and materials and dancing with colour. Narrow light boxes punched with vibrant filters slither through the wall and a giant translucent print creates a stained-glass window. Entitled Fontanelle, after the soft gap in a newborn baby’s skull, the large monotype print is placed on what was once a back wall and has been removed to reveal a window. Khorramian creates monotypes by applying oil paint on polypropylene or glass and transferring it to paper. The effect is organic and surprising, producing a kaleidoscope of unfamiliar forms.

During the pandemic, Khorramian made thousands of masks for those in need and the remnants of the fabric clamber up her tapestries like spines. And, with names like Glass Person, Jag Lady and Totem of a Deity, her floor-to-ceiling banners transform into revered individuals in a futuristic hall of fame where our heroes upcycle and wear dresses. Eventually, Khorramian appears and offers me a piece of dark chocolate. Perhaps this was the post-Covid world of which I’ve dreamt.

The Vasseur Baltic artists’ award 2022 is at Baltic, Gateshead, until 2 October.

From the The Guardian website.