Al Qasimi’s shift to black-and-white in Toy World at The Third Line, Dubai burdens her usually visceral use of colour with a spectral weight

Farah Al Qasimi’s photographs have long been associated with the clashing aesthetics of an unfolding Gulf futurism, in which living culture fuses with accelerative global capitalism. Living Room Vape (2016), for example, shows a domestic, Emirati space embodying the contemporary opulence of a gilded, Silk Road transculturalism. Colour and pattern play a visceral role in the artist’s imagery. During the pandemic, the move towards muted palettes and depictions of open spaces in images like Woman and Snail (2022) – a blue-scale silhouette of a snail resting on a woman’s arm against the backdrop of the sea – signalled a palpable shift. Toy World reflects another change, with black-and-white photographs (all undated) appearing for the first time in the artist’s photographic installation. They are arranged in linear sequences, like hieroglyphic texts: one line features a burning palm frond; a figure embracing a horse; an American shop window whose title, Terrorist Hunting Permit, draws attention to a sticker describing just that in the photo; a young marine in profile; and a view of the temple of Artemis at Jerash, Jordan.

‘Black and white images automatically historicize,’ Al Qasimi tells Sarah Chekfa in an essay by the latter accompanying the show, offering some insight into the artist’s engagement with the genre. A sense of history certainly pervades Toy World. Rather than installing images on wallpaper composed of blown-up prints to create her characteristic multicoloured compositional mashups, here the photographs are presented alongside smaller colour printouts and black-and-white photocopies – plus a few plastic flowers here and there – taped to the wall at varying heights, and depicting, among other things, ancient coins. One photocopy shows portraits from Wilfred Thesiger’s 1959 book Arabian Sands, of guides who accompanied Thesiger on his travels across Rub’ al-Khali or the ‘Empty Quarter’, the world’s largest sand sea, which connects Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman and the UAE. Those portraits also appear in the mixed-media photographic collage Wingspan (2024), a density of images that traverse time while remaining anchored to context: from plaster stucco fragments discovered in Sir Bani Yas, where the earliest known evidence of Christianity in the UAE exists in the form of a church, monastery and courtyard houses dating to the seventh and eighth centuries; to an advertisement for a ‘Gulf War U.S. Army Infantry Woman’ toy named Sandy.

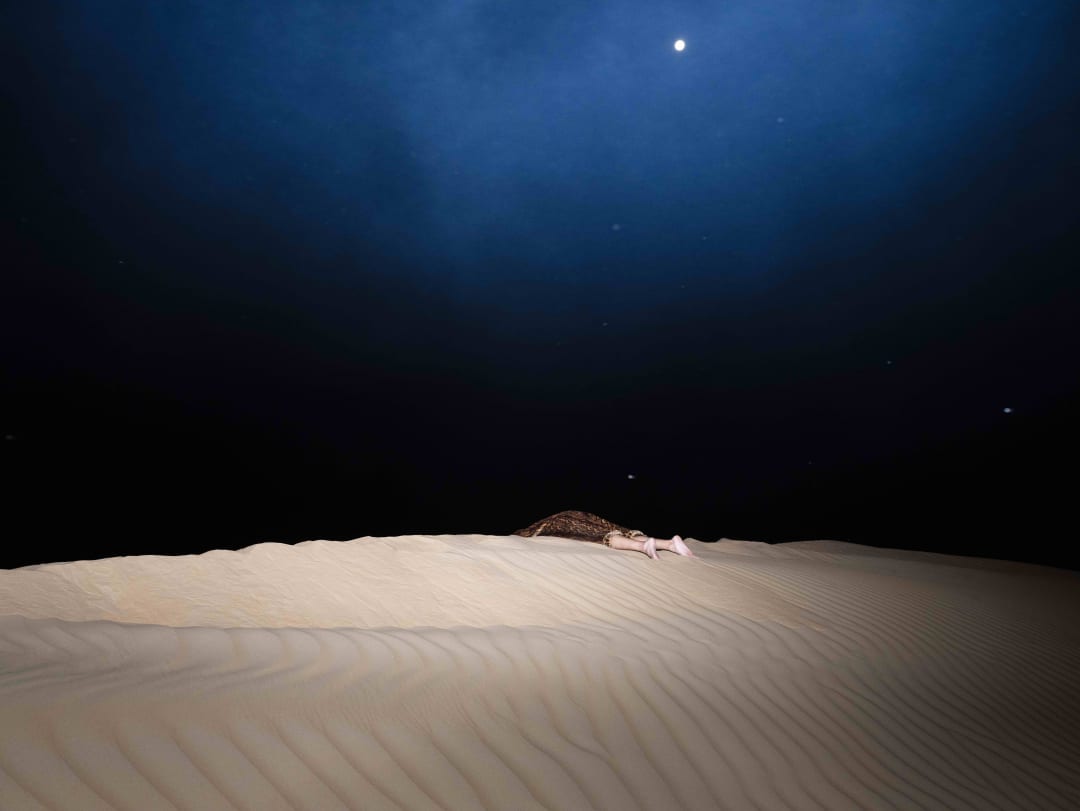

With its reference to Rub’ al-Khali, Wingspan functions like an index for Toy Story, where every image, object and frame articulates a sense of haunted time. Take one triptych of black-and-white images, of a camel’s fly-covered head bookended by the concrete shell of a house under construction and a smattering of camel bones on the ground: the sequence recalls Al Qasimi’s video Um Al Dhabaab (Mother of Fog) (2023, not shown here), where two sisters from twenty-first-century Ras Al Khaimah connect with the spirit of a nineteenth-century anti-colonial fighter from that region, through his remains. Amid these associative excavations, each black-and-white sequence burdens the colour images around them with a spectral weight. One colour photo of a figure draped over the edge of a moonlit sand dune (Sand Dune, 2023) echoes a video screened on a TV monitor showing a woman in red crawling and rolling down a desert incline repeatedly. Another colour video shows mechanical plastic toys moving across a tiled floor: a crawling spiderman with plastic flowers tied to his ankles carries a gun, as a walking cow drags a green bottle behind it. They move in aimless circles to an uncanny symphony of mechanical moos and gunshots: an uncanny loop.

From the ArtReview website