-

Anuar Khalifi

Mirror Ball

-

The Third Line is pleased to announce our second solo exhibition with Spanish-Moroccan artist Anuar Khalifi. The exhibition, titled Mirror Ball, will debut a unique sculpture together with a series of richly detailed and vibrant paintings that continue the artist’s ongoing exploration into the complexities of personal identity and the experience of living between two worlds, both seen and unseen.

-

Anuar Khalifi: Life as a Mirrorball

Omar Kholeif -

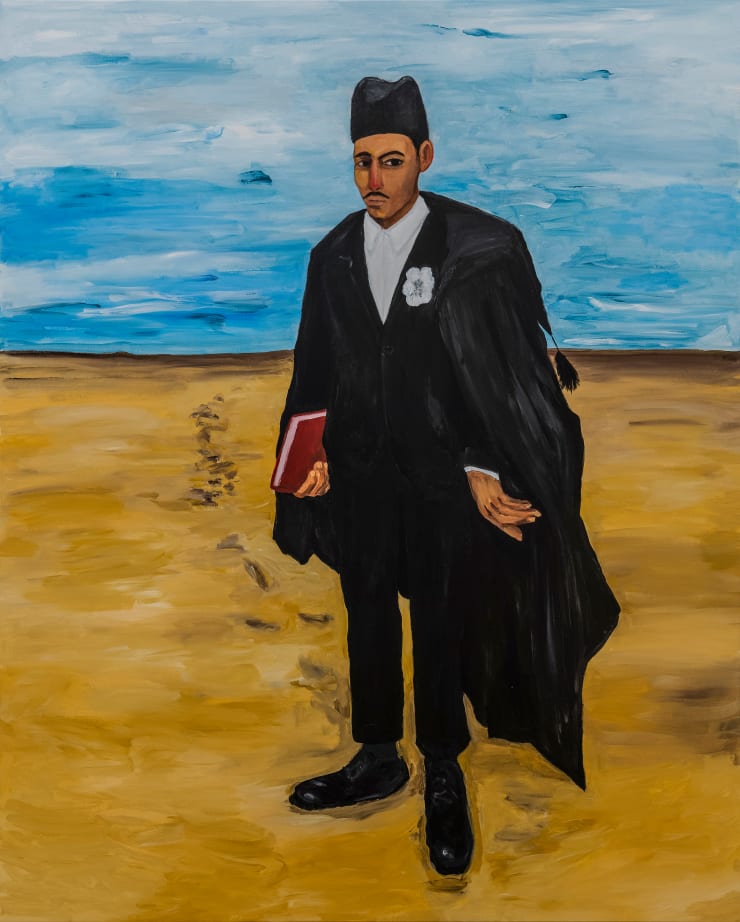

Anuar Khalifi

Erase my Footsteps, 2022

Acrylic on Canvas

200.00 x 150.00 cm. -

-

Khalifi’s protagonist likewise pulls the eye in and around the details. With quiet observation, the onlooker arrives to the centrifugal point of the body. Peer closer and one’s ocular sensibilities are situated around the duality of the gentleman’s flowing white clothes and the incandescent blue backdrop behind him. On inspection, it appears that Erase My Footsteps could possibly be an inversion of Henri Matisse’s Blue Nude II (1952), a series of gouache painted paper cut-outs, stuck to paper, and mounted onto canvas. In Blue Nude II, the limbs of Matisse’s female body appear as if they were rising from the canvas. An unusual contradiction: She does not embody the subjugated passivity assumed of a naked female model. Like Matisse, Khalifi deploys the colour blue as a means to signify volume and distance—collapsing assumption of dimension and scale.[1]

Most spectators will likely hold an unceasing desire to comprehend the biography of the artist who has made the paintings before them. Who is the artist, Anuar Khalifi? On first encounter, I assumed that he might, and indeed is, a relative of mine, his surname a variation of my own. Khalifi/Khalifa and its variants is assumed to be a tribal cognomen that can be traced, depending on one’s principle of truth-telling as descending from individuals who roamed across the African continent in B.C. and settled in Andalucía. In some realm of fiction, they are the ones who ascribed the state of California with its name.[2] The artist, who at times appears as a quiet sanctum of zen, will concede that his lived experience—being of and from two inter-connected and contested places, forms a philosophical point of inquiry. Morocco and Spain—that at the narrowest expanse—from border to border, may only be 18.5 KM in distance apart, are nonetheless, each subject to radically divergent histories of visual culture and imagination.

In the English-speaking cultural imaginary attendant to modernism, Morocco, and particularly, Tangiers, where Khalifi often lives and works, has served as an extended site of fancy for authors such as George Orwell and Paul Bowles, through to Beat-era poets, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs, as well as the infamous life of Jean Genet, who is buried in the fishing village of Larache. There are also the ethereal mythologies crafted in Hollywood films including, Casablanca (1942) and Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956). In these guises, Morocco has functioned as a seat of escape and reprieve for foreigners—for those once perceived as literary dissidents, or in the movies, as a seeming safe haven, that is, up until everything goes wrong. After all, Hitchcock’s movie weaves its subjects from and through local markets, only to serve as a stage for a kidnapping.

Morocco in popular culture has been referred to as a place of “folly”[3], and in some cases as a conducive environment for sexual awakening[4], or as a seat for white people’s counter-cultural heritage and expression to be explored[5]. Of all the nations in North Africa and West Asia, it did not fall under Ottoman rule. Rather, Morocco, a protectorate of France, and to a lesser degree, Spain, up until its independence in 1956, was an anomaly for “literary pilgrims” amidst the shroud of disputed colonised states in Africa.[6] The mythologies of popular fantasy have for a measure of time, however, obscured Morocco’s own contributions to literature and the visual arts.[7] From the 1950s to the 1970s, for example—the peak of the period that would come to be referred to as the modern era and late modernism, Moroccan cultural practitioners coalesced under the umbrella of projects such as the publication, Souffles—an illustrated experimental journal of Leftist writing and visual expression from across North Africa and West Asia.[8] Within these pages a form of “tricontinental postcolonial thought” was posited by artists and authors such as Etel Adnan and Mohamed Melehi, as well the likes of Tahar Ben Jelloun, Sembene Ousmane, encompassing illustrations by artistic voices who emerged from what is now recognised as the illustrious School of Fine Art, Casablanca, with notable graduates including, Mohamed Chabâa and Farid Belkahia.[9] The artists associated with the school were mostly painters. Together, they constellated a movement that was articulated as evincing a period of “re-birth” and concentrated experimentation in the nation.[10]

-

-

Entering an exhibition by Anuar Khalifi—be it within the confines of the artist’s studio in Barcelona, Tangier, or at The Third Line Gallery in Dubai, conjures a spirit of awakening—a summoning of the aura, as much as the interpretive aspects of the senses.

Entering an exhibition by Anuar Khalifi—be it within the confines of the artist’s studio in Barcelona, Tangier, or at The Third Line Gallery in Dubai, conjures a spirit of awakening—a summoning of the aura, as much as the interpretive aspects of the senses. One’s eyes seek and attempt to compose figures emerging from luminous blue and green colour fields, deciphering the artist’s pictures, only to retract. For occupying Khalifi’s world is to be occupied by the phantasms of and in his canvasses, who in their seeming stillness, their errant silence, rupture perception and with it, the expected semblance of linear narrative or meaning. It feels apt to emphasise Freud’s expressions of the “fantasme” in its broadest sense. For to invoke this is to create a world for the hushed animism of Khalifi’s exuberant characters. [11] In these canvasses, they can be seen dreaming and hallucinating, imagining, or to invoke Kristen Scheid’s adoption of the “fantasmic”, as individuals who are “encountering” a world of their own culturally-situated form and making.[12] Part of Scheid’s narration, which examines post-independence Lebanon in the first half of the 20th century, discusses how art objects, particularly ones that “negotiate” the dimensions of variable cultural histories, create a form of “sociality” amongst citizens, as well as the various aesthetic conduits in and of their making.[13]

-

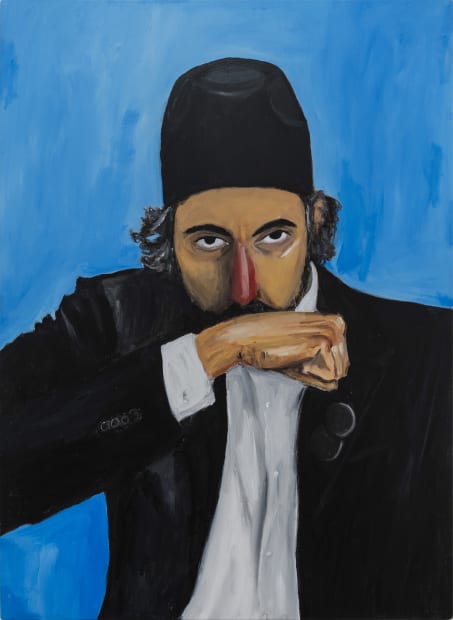

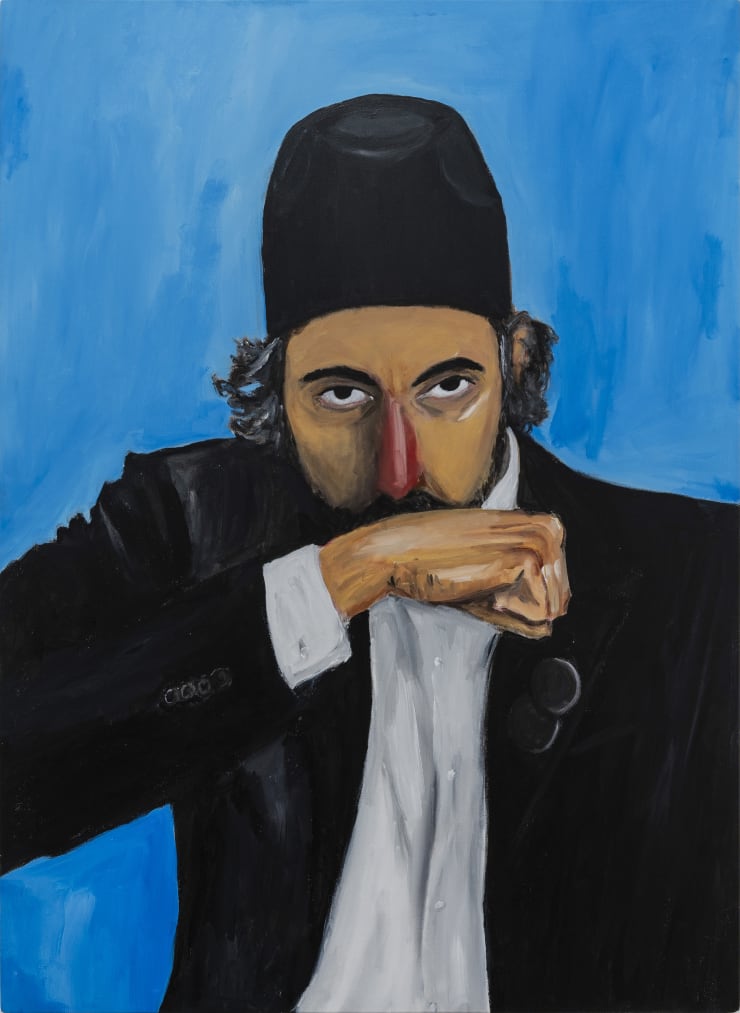

Anuar Khalifi

Anuar Khalifi

Smellfie, 2023

Acrylic on Canvas

106.00 x 77.00 cm. -

-

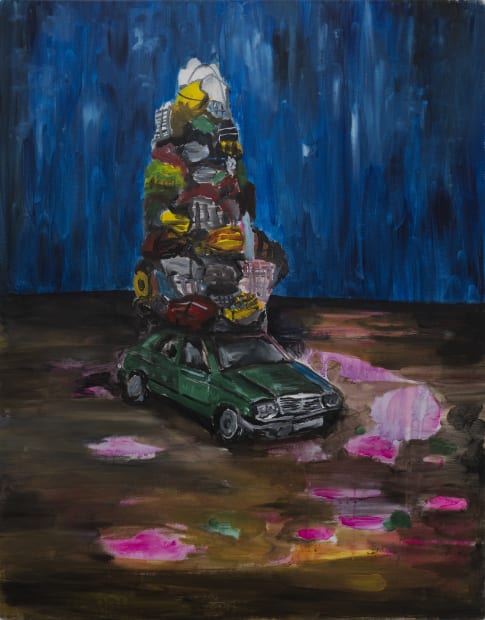

Anuar Khalifi

Anuar Khalifi

The Trip, 2022

Acrylic on Canvas

110.00 x 86.00 cm. -

Configuring one’s identity, the negotiation with the weight of two colonising cultural histories flourishes in Transmission (2022). Here, a young boy, whose feet, and hands, appear suggestive of a Sphinx-like other-worldly character, can be seen wrestling with an individual in Sufi dress. Queried about the duality of the two bodies before me, Khalifi expressed the manner in which we “move” and morph into different selves, the experience of borrowing and inheriting different cultures, over the duration of one lifespan. Equally, we constellated around the idea of “commanding common ground”—two individuals from different paths, in the end, can choose to resolve the difference attributed to them, as opposed to remaining in the flux of feeling wanton, empty, or longing.[15] Loneliness, once discussed in the medical sciences as purely subjective—of being a “minor” condition, has now become understood as a “syndrome”. It is one that has become unrelenting in the lives of those who are most vulnerable, or prone to harm.[16]

-

It was at this point in our discussion that I homed in on the diptych Talwin and Tamkin (2022). On one panel, the eye, voyeuristically enters the bedroom of a male figure as they cast their gaze over abstracted renderings of Francisco Goya’s images of wartime violence. To his left is an empty landscape, its meaning still in flux. It is a scene, from Khalifi’s village in Morocco. I turn around and there is another image, the unfinished image from within Talwin and Tamkin is now made animate as Souvenirs (2022). The fleeting panorama from Talwin and Tamkin is now occupied with the protagonist from an earlier work, The Wounded Raver (2021). Anchored on a rickety boat, with his belongings, the wounded raver dressed in his signature Arsenal football top, is accompanied by a maquette of a Maqam. In the backdrop behind him just at the end of my line of sight is yet another Maqam, a point of waiting, or return. A Maqam in Arabic language holds multiple meanings. It is a shrine or tomb where a holy Muslim person is buried, but it is also a melody type, or a space, or site for the improvisation of music. The latter, helps foster another site of encounter of and for oneself, a seat of and for becoming, where expression is found through the experience of constant play, a feeling conjured in the portrait, The Weight of an Ant (2022).

-

The ocular pull created by Anuar Khalifi figures speak to a form of embodiment where solitude becomes a space of intimate knowing, one that enables an assured animism with others. Loneliness, the absence of home, or the longing will to belong, thus become propulsive questions that enable one to reclaim public space as opposed to suffocating queries. This act of recuperation is not dissimilar to the one that emerged in the early 1970s when Black American artists resisting a call for a “Black aesthetic” used abstraction and colour as a means to create their own space in the public arena of late modernism.[17] And with that, enters Khalifi’s Mirror Ball (2022). Here, a dance of bodies in deep blue, soldered together, will move in playful dance, perhaps an infinitum. “There is no axis” noted Khalifi of this work. Invoking Sufism, he noted, “each one of us is a reflection of another.”[18] For a mirror, like a mirror ball, with its reflections of light, fashions colour, dreamscapes, and possibilities that expand beyond the contours of any single experience. It is an active, searching demand for constant beginning.

-

-

Worklist

-

Anuar KhalifiTransmission, 2022Acrylic on Canvas175.00 x 200.00 cm.

Anuar KhalifiTransmission, 2022Acrylic on Canvas175.00 x 200.00 cm. -

Anuar KhalifiGreen for the Eyes, 2023Acrylic on Canvas46.00 x 30.00 cm.

Anuar KhalifiGreen for the Eyes, 2023Acrylic on Canvas46.00 x 30.00 cm. -

Anuar KhalifiTalwin and Tamkin, 2022Acrylic on Canvas190.00 x 135.00 cm. (each)

Anuar KhalifiTalwin and Tamkin, 2022Acrylic on Canvas190.00 x 135.00 cm. (each)

Diptych -

Anuar KhalifiThursday, 2023Acrylic on Canvas33.00 x 43.00 cm.

Anuar KhalifiThursday, 2023Acrylic on Canvas33.00 x 43.00 cm. -

Anuar KhalifiInterim, 2023Acrylic on Canvas157.00 x 114.00 cm.

Anuar KhalifiInterim, 2023Acrylic on Canvas157.00 x 114.00 cm. -

Anuar KhalifiSirr, 2023Acrylic on Canvas200.00 x 160.00 cm.

Anuar KhalifiSirr, 2023Acrylic on Canvas200.00 x 160.00 cm. -

Anuar KhalifiThe Hundred Step, 2023Acrylic on Canvas200.00 x 160.00 cm.

Anuar KhalifiThe Hundred Step, 2023Acrylic on Canvas200.00 x 160.00 cm. -

Anuar KhalifiMirror Ball, 2022Acrylic on Canvas175.00 x 200.00 cm.

Anuar KhalifiMirror Ball, 2022Acrylic on Canvas175.00 x 200.00 cm. -

Anuar KhalifiSouvenirs, 2022Acrylic on Canvas112.00 x 87.00 cm.

Anuar KhalifiSouvenirs, 2022Acrylic on Canvas112.00 x 87.00 cm. -

Anuar KhalifiThe Weight of an Ant, 2022Acrylic on Canvas250.00 x 175.00 cm.

Anuar KhalifiThe Weight of an Ant, 2022Acrylic on Canvas250.00 x 175.00 cm. -

Anuar KhalifiErase my Footsteps, 2022Acrylic on Canvas200.00 x 150.00 cm.

Anuar KhalifiErase my Footsteps, 2022Acrylic on Canvas200.00 x 150.00 cm. -

Anuar KhalifiThe Trip, 2022Acrylic on Canvas110.00 x 86.00 cm.

Anuar KhalifiThe Trip, 2022Acrylic on Canvas110.00 x 86.00 cm. -

Anuar KhalifiSmellfie, 2023Acrylic on Canvas

Anuar KhalifiSmellfie, 2023Acrylic on Canvas

106.00 x 77.00 cm. -

Anuar KhalifiObserve/d, 2022Acrylic on Canvas175.00 x 125.00 cm. & 103.00 x 66.00 cm.

Anuar KhalifiObserve/d, 2022Acrylic on Canvas175.00 x 125.00 cm. & 103.00 x 66.00 cm.

Diptych

-

-

About Anuar Khalifi

Self-taught artist Anuar Khalifi was born in 1977 in Lloret de Mar, Spain. Currently based between Barcelona and Tangier, Khalifi creates richly detailed and vibrant paintings that reward the keen eye with their captivating layers of meaning. Within these layers, the artist explores a wide range of themes such as identity, duality, diaspora, orientalism, colonialism, extremism, and consumerist society.

His work has been exhibited in a number of solo and group exhibitions including: Perpetual Inventory, Volume 1: An Exercise in Looking, Curated by Dr. Omar Kholeif, The Third Line, Dubai, UAE (2022/2023); In The Heart Of Another Country, Deichtorhallen Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany (2022); Art, a serious game, MACAAL, Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden, Marrakesh, Morocco (2022); Personal Mythologies, Galerie Julien Cadet, Paris, France (2020); Forever Is A Current Event, The Third Line, Dubai (2019); Dust, Roses & cockroaches, Galerie Shart, Casablanca, Morocco (2018); Now, Biennale, Marrakech, Morocco (2012); Blast, Mastermind (GVCC), Casablanca, Morocco (2012); Boys don't cry, Artingis, Tangier, Morocco (2011); Fast Food, Les Insolites, Tangier, Morocco (2011).

Khalifi’s works are in the collection of MACAAL, Musée d'Art contemporain africain Al-Maaden, Marrakech, Morocco, and Sharjah Art Foundation, Sharjah, UAE.

-

About Omar Kholeif

Dr Omar Kholeif CF FRSA aka Dr. O is an author of prose and poetry, a historian of the academy and its peripheries and a curator of vanquished and suppressed archives. They have worked as a broadcaster, filmmaker, editor, publisher, and museum director. Over the last two decades, their work has concentrated on the evolving nature of networked image culture in relation to intersectional questions emerging in the field and study of ethnicity, race, and gender. Their lines of inquiry have come to life in over 60 exhibitions, and in nearly 40 authored, co-authored, and/or edited books, which have been translated into 12 languages. Dr. Kholeif was co-curator of Sharjah Biennial 14: Leaving the Echo Chamber and currently serves as Director of Collections and Senior Curator, Sharjah Art Foundation, UAE. Their much-anticipated monograph, Internet_Art: From the Birth of the Web to the Rise of NFTs is published by Phaidon in early 2023, Visit: www.omarkholeif.com

-

Reference List for 'Anuar Khalifi: Life as a Mirrorball' by Omar Kholeif

[1] Karl Buchberg, Nicholas Cullinan, Jodi Hauptman and Nicholas Serota (2014) ‘The Studio as Site and Object’. In Buchberg, Cullinan, Hauptman and Serota (eds.) Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, pp: 11-15.

[2] Ruth Putnam and Herbert Ingram Priestley (1917) California: The Name. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Available at: https://archive.org/details/cu31924008278347/page/n7/mode/2up, accessed 27 March 2023.

[3] Nigel Andrews (2017) “Mythical Morocco”. The Financial Times, June 21, 2017. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/1a8543b6-1e10-11dc-89f7-000b5df10621, accessed 29 March 2023.

[4] Edmund White (1994) Genet: A Biography. New York: Vintage Books.

[5] Sam Jordison (2010) “Beat and dust: Tangier’s Tang history”. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2010/nov/23/tangier-william-burroughs-naked-lunch, accessed 28 March 2023.

[6] Hisham Aidi (2019) “So Why Did I Defend Paul Bowles?” The New York Review of Books (December 20, 2019).

[7] Gonzalo Fernández Parrilla and Eric Calderwood (2021). “What is Moroccan Literature? History of an Object in Motion. Journal of Arabic Literature, 16 April 2021. Also see: Julie Scott Meisami and Paul Starkey (eds.) (2010). London: Routledge. Pages: 421-531.

[8] Claudia Esposito (2020) “Traces of Souffles: on cultural production in contemporary Morocco”. Contemporary French Civilization. Volume 45, Number 3-4.

[9] Olivia C. Harrison and Teresa Villa-Ignacio (2015) “Souffles Anfas for the new millennium”. IN O.C. Harrison and T. Villa-Ignacio (eds.) Soufles Anfas: A Critical Anthology from the Moroccan Journal of Culture and Politics. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. Pages: 18-23.

[10] See the School of Casablanca Archives, a project of KW, Sharjah Art Foundation and Zamân Art and Publishing, and Tate St. Ives here: https://schoolofcasablanca.com/casa/. Accessed 29 March 2023.

[11] Herman Rapaport (1994) “Theories of the Fantasm”. Between the Sign and Gaze. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Pages: 17-22.

[12] Kirsten L. Scheid (2023) Fantasmic Objects: Art and Sociality from Lebanon, 1920-1950. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. Pages: 42-89.

[13] Ibid. Pages: 13-16.

[14] Conversation with the artist, Anuar Khalifi, 14 March 2023.

[15] Conversation with the artist, Anuar Khalifi, 14 March 2023.

[16] Maike Luhman, Susanne Buecker & Marilena Rüsberg (2023) “Loneliness across time and space”. Nature Review Psychology. Volume 2. Pages: 9-23.

[17] Darby English (2016) 1971: A Year in the Life of Color. London and Chicago: Chicago University Press.