-

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige

Messages with(out) a code8th March - 26th April 2022

-

The Third Line is pleased to present a solo exhibition by artists and filmmakers Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige. The exhibition proudly debuts The Third Line's newly renovated space, which is being unveiled alongside this show. Messages with(out) a code presents a selection of new and seminal pieces from their ongoing project Unconformities, which began in 2016 when the artists started collecting a series of earth core samples that revealed the subterranean worlds of cities omnipresent in their personal imaginaries: Athens, Paris, Beirut and Tripoli.

-

-

-

Interview between Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige and Writer and Curator, Shumon Basar

February 2022

-

Shumon Basar:

When I first saw the word you use for this cycle of work — Uncomformities — it felt familiar, but then, I realised I was mistaken. It's one of those words that gets stranger the closer you get to it. Could you tell us what it actually means?

-

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige:

Unconformities is a geological term indicating temporal ruptures, natural disasters and geological movements. It is a discontinuity — a gap in time — the moment when two sequences separated in time meet because a catastrophe has changed the natural order of geological strata.

Unconformities is also the title of our ongoing project that launched in 2016. This project reveals the underground natural and manmade histories that lie beneath several cities through drilled core samples which have been extracted from construction sites and are usually disposed of. Such sedimentations and deposits question the possible narratives and representations of the history of cities, and allow us to access the invisible and buried remains of subterranean worlds and its multiple temporalities. Living in a region where we are continually in disruption, it is an echo of how we can continue to create and to narrate, despite the discontinuity of our history. Diving into the vertigo of time with archaeology and geology helps us in such times of collapse and chaos.

-

Living in a region where we are continually in disruption, it is an echo of how we can continue to create and to narrate, despite the discontinuity of our history.

-

Shumon Basar:

So, you enlist the collaboration of an archaeologist and geologist and, together, you recuperate these "core samples" (which are vertical, cylindrical sections through the earth) in three cities that have mattered to you: Beirut, Paris and Athens. We see some of the material findings in the chapter Palimpsests. What drew you to this confluence of matter, time and urban memory?

-

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige:

We've always been interested by history, its representations, its rewritings, and the constructions of the “imaginary”. In this project, it started with an encounter with a friend, Philippe Fayad, who drills soil and analyses it for real estate projects. We started to go to construction sites with him and, suddenly, we had access to what lies beneath our feet. We are fascinated by these cores, stones and residues that are brought up from deep in the earth and put into chronological order in boxes. We don’t know how to read this succession of historical and geological events, and so we need an interpreter, which we found in Hadi Choueiri. Hadi is an archaeologist in charge of a large construction site opposite our house. He is fascinating, and he shares his passion with us. By having access to various archaeological findings with Hadi, we find ourselves at the opposite end to our starting point; when we began producing images and films, in Beirut in the 90s, with this necessity to keep traces and to counter the erasure of the war in our collective history. We realised that, paradoxically, the madness of the reconstruction and real estate speculation led us to have greater access and a better understanding of Beirut’s history compared to a more protected city, such as Paris. In these cores, history appears not as successive chronological strata. Nor is history a collection of layers where the more ancient residue can be found at the bottom and the most recent at the top. All is upside down, chronology is disturbed. History appears as complex actions, a diverse mix of traces, epochs and civilisations. It is a constant cycle of destruction and construction, catastrophe and regeneration... Cities mix, erase, bury and recycle the same stones over and over again... as a vertiginous palimpsest.

-

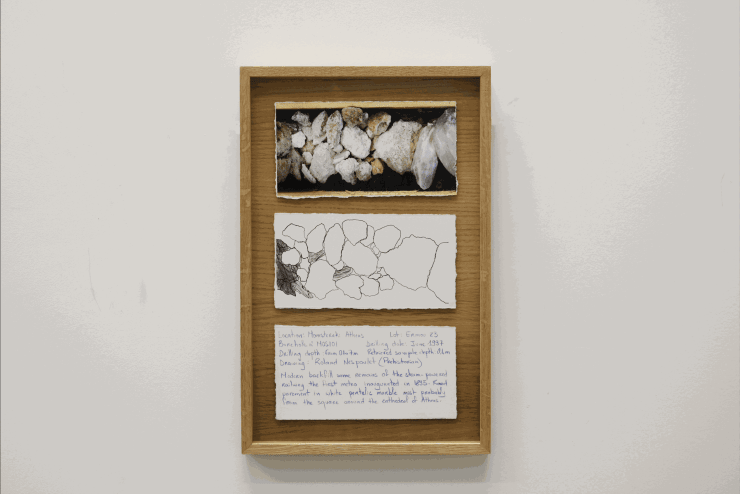

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige, Time Capsules, Monasteraki B3, 2017, Core samples in experimental resin, 155 cm x 15 cm diameter

-

Shumon Basar:

The French novelist, Alain Robbe-Grillet, who led the "nouveau roman" movement in Paris in the 1950s, had been an agronomist before he turned to literature. He, too, used to take core samples of the earth, and somehow, knowing this helped me understand his prose: which is analytical, dispassionate, forensic. You've described organising the archaeological matter from the digs as "like film rushes that need editing." What do you mean by this, and, how is this sentiment portrayed in your works, Time Capsules and Trilogies?

-

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige:

We choose the best moments of the historical events that these stones and sediments reveal to us, and we preserve these stories in a completely chronological way.

As filmmakers, we see a lot of connection between the making of films and the exploration and organisation of the very important materials recovered by coring. Dozens of cores are taken out of the ground at different depths and analysed before being thrown away. They are like found footages, so to speak, because we don't dig them; we recover them. But, they are not what you would call "ready-made" either.

When we recover these dozens of boxes, we re-sculpt them with archaeologists and geologists who know the terrain well and have already excavated and analysed it. They are the editors, if we want to continue the analogy. We choose the best moments of the historical events that these stones and sediments reveal to us, and we preserve these stories in a completely chronological way. In the Time Capsules, we have a sequence that will capture the mutations of cities and places which we fix in transparent experimental resin so that we can see and make visible this buried part of history. We also photograph this sequence and give it to archaeologists, prehistorians and natural history illustrators who then redraw it and highlight the important parts, giving us a glimpse of what to look for. In Trilogies, we add what remains of the stories they tell us using our imagination. It's not scientific but more possible narratives, poetic moments.

Our practice as filmmakers and artists has always been to keep a trace, to give a visibility to the latent, to what is there but that we’re not able to see, to capture a moment that is already evanescent, the recording of what disappears.

-

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige, Installation view at The Third Line, 2022

-

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige:

To approach history, we need the panoramic, the macro and the microscopic, the drone captures and the details; the infinitely small and the infinitely large…

The video, Palimpsests, plays with scales of time and size. We move from the massive that confronts the miniscule, horizontality and verticality. The drone has changed the approach of archaeology a lot, but has also created the possibility to scan objects and approach the micro part of it. The drone and the microscopic represent what the naked eye cannot see, questioning the conditions of our own vision. These are not naturalistic; they are not what humans see. They are like monstrous visions that provoke a kind of vertigo.

It reminds us of a character in Maupassant's Horla who says: "But our eye, gentlemen, is such an elementary organ that it can hardly distinguish what is indispensable to our existence. What is too small escapes it, what is too big escapes it, what is too far escapes it”. There is always something that escapes, that cannot be complete, one and the other, one or the other.

It is the notion of the fantastic which is, first and foremost, a matter of vision, of what is perceptible and what appears, what remains in the shadows and what is latent, what escapes us. This is what has always fascinated us. It questions forms of representations and expresses these tense interactions between the buried remains and the arising history from the past to our troubled present.

-

-

Shumon Basar:

The 2019 part of Uncomformities is called A State. It's based around an artificial geology, that is, a massive mountain made from 25 years of densely piled trash, outside Tripoli, Lebanon. You use the term "technofossil" here. What is that? And can you explain how the incredible images in A State are composed?

-

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige, Installation view at The Third Line, 2022

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige, Installation view at The Third Line, 2022 -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige:

The term “technofossil” was used by Professor Jan Zalasiewicz to describe the material footprints that humans will leave behind.

Treatment of waste is the centre of questions regarding the inheritance of the planet, economic and environmental management and “The Great Acceleration”.

A State is a series of three images composed from a very peculiar drilling core sourced from an enormous rubbish dump in Tripoli, Lebanon. A landfill bordering the sea and exposed to the elements that has been accumulating waste for over a period of twenty-five years — an entire generation! This sedimentation has radically altered the local landscape, and today forms hills that rise forty-five meters above sea level.

These images are composed from multiple digital photographs juxtaposed and superimposed, taken at different focal points to obtain a more realistic, hyper-realistic image.

Extremely pictorial still-lives, very defined as the material disintegrates and becomes abstract. They are like shredded shreds, organic materials that disappear. All that remain are the technofossils; it is what we leave behind.

They resist time and remain long after their surrounding landscapes disappear.

-

Shumon Basar:

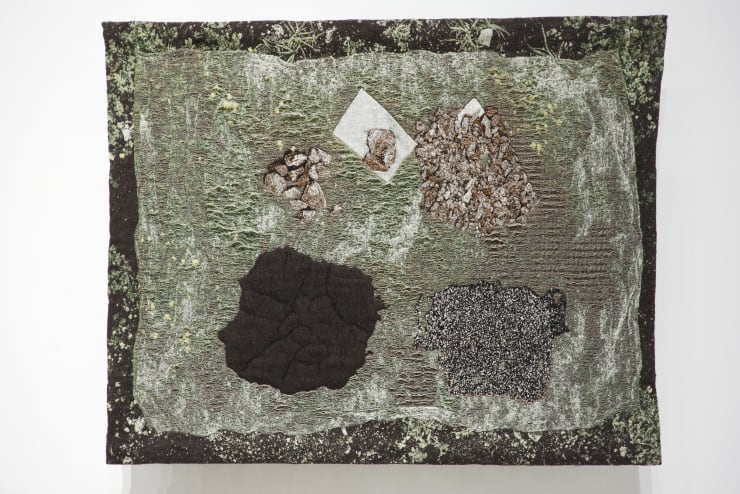

This brings us to the present moment. You've been working with weavers to make new tapestries. You call them, Message with(out) code. What do you mean by this? And what have you discovered in the process of fabricating the tapestries that makes links to complex archaeology and ruptured history?

-

-

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige:

Message with(out) a code comes from a practice discovered on an archaeological site. Caught up in the urgency of a situation, archaeologists have invented their own methodology, their own code.

With sieves of different sizes, they take samples to detect the greatest density of past human presences, details, traces of baked clay, seeds… They lay stones and soils out on the ground on flat surfaces to take readings, sedimentations and flattened densities as if the whole of time became one-dimensional.

Fascinated, we document the sieves observed photographically. The sensation is similar to that of an autopsy. The entrails of time and history in the open air offered to our eyes — messages without codes — which need the expertise of others to read. These photographs obsessed us, we don't really understand them, and for a very long time we hung them on the walls of our studio in Beirut.

They were shredded at the time of the explosion on August 4th 2020, which destroyed our entire studio and the works that were there.

The images inhabit us, as if they contained a code that would help us out of the chaos by expressing it through a language, an optical geometry. Inspired by Gilles Deleuze writings; it is the contour. The forms have contours that contain chaos by expressing it but also, in a certain way, by exposing it...

Tapestry imposes itself on us as a medium. It implies a weaving, a juxtaposition of materials. It is an ancestral technique — a tradition — which can render the density of these archaeological compositions. Choosing colours from a multitude of possibilities and materials, the complexity of layers, making and unmaking, knotting and unknotting, restoring the link...

Weaving is a way of restoring something that we have lost. A loss that we all feel now — perhaps even more painfully — given the recent events in Lebanon. Weaving what has been undone, recovering the texture, the transparency, the different layers and perspectives. Transforming seems to be a way of finding meaning again, and of reconnecting to the infinite and long time in the face of the shorter temporality, and allow ourselves to free from it.

-

-

Tapestry imposes itself on us as a medium. It implies a weaving, a juxtaposition of materials. It is an ancestral technique — a tradition — which can render the density of these archaeological compositions.

-

About Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige were both born in Beirut, Lebanon in 1969 and currently live and work between Beirut and Paris. They collaborate as artists and filmmakers, creating thematic and formal links between photography, video, performance, installation, sculpture, and cinema. Over the last fifteen years, the duo has particularly focused on the fabrication of images and the construction of imaginaries. Using personal or political elements to record stories that were stifled in prevailing history, Hadjithomas & Joreige explore the relationship between image and narrative.

Their artworks are part of major private and public collections including British Museum (London), Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris), Fond national d’art contemporain (France), MCA Chicago, Museum of Modern Art (Paris), Sharjah Art Foundation (UAE), Mamco (Geneva), Solomon R Guggenheim (New York), and Victoria & Albert Museum (London). They presented their works in solo exhibitions at Haus der Kunst (Munich), HOME (Manchester), Museum of Modern Art (Paris), IVAM (Valencia), Jeu de Paume (Paris), MIT List Visual Arts Center (Cambridge), Powerplant (Toronto), Sharjah Art Foundation (UAE), Beirut Exhibition Center (Beirut), Villa Arson (Nice) and many more. They have also participated in many group exhibitions in museums and art centres around the world, such as Ashkal Alwan (Beirut), KW Berlin, MOMA (New York), SFMOMA (San Francisco), Red Brick Art Museum (Beijing), Singapore Art Mu-seum, Tate Modern (London), Whitechapel Gallery (London), and ZKM (Karlsruhe). They participated in many biennials such as Taipei, Venice, Istanbul, Lyon, Sharjah, Kochi, Gwangju, and the Paris Triennale.

To view their full biography and CV, please click here

-

About Shumon Basar

Shumon Basar is a writer and curator. He is author of the books The Extreme Self: Age of You and The Age of Earthquakes: A Guide to the Extreme Present, both with Douglas Coupland and Hans Ulrich Obrist. Together, they co-curated the large-scale exhibition Age of You at MOCA Toronto and Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai. Basar is also Commissioner of the Global Art Forum in Dubai; a member of Fondazione Prada’s “Thought Council;” and has editorial/advisory roles at the magazines TANK, Bidoun, 032c and Flash Art.

-

Worklist

-

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeMessage with(out) a code (1), 2022Tapestry, different kinds of yarn130 x 170cm (approx)Edition 1 of 5, 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeMessage with(out) a code (1), 2022Tapestry, different kinds of yarn130 x 170cm (approx)Edition 1 of 5, 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeMessage with(out) a code (2), 2022Tapestry, different kinds of yarn130 x 170cm (approx.)Edition 1 of 5, 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeMessage with(out) a code (2), 2022Tapestry, different kinds of yarn130 x 170cm (approx.)Edition 1 of 5, 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeMessage with(out) a code (3), 2022Tapestry, different kinds of yarn130 x 170cm (approx.)Edition 1 of 5, 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeMessage with(out) a code (3), 2022Tapestry, different kinds of yarn130 x 170cm (approx.)Edition 1 of 5, 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeA State - Borehole 1, 2019Digital Photography235 x 140cmEdition 2 of 4, 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeA State - Borehole 1, 2019Digital Photography235 x 140cmEdition 2 of 4, 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeA State - Borehole 2, 2019Digital Photography212 x 140cmEdition 2 of 4, 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeA State - Borehole 2, 2019Digital Photography212 x 140cmEdition 2 of 4, 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeA State - Borehole 3, 2019Digital Photography230 x 140cmEdition 2 of 4, 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeA State - Borehole 3, 2019Digital Photography230 x 140cmEdition 2 of 4, 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTime Capsules, Monasteraki B3, 2017Core samples in experimental resin155 x 15 x 15 cmUnique

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTime Capsules, Monasteraki B3, 2017Core samples in experimental resin155 x 15 x 15 cmUnique -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeMonasteraki 1 (0.4m) , 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 28.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeMonasteraki 1 (0.4m) , 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 28.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 2 (0.8m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 43.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 2 (0.8m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 43.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 3 (1.1m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 28.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 3 (1.1m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 28.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 4 (2.1m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 21.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 4 (2.1m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 21.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 5 (2.5m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 30 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 5 (2.5m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 30 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 6 (2.7 - 3.4m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 60.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 6 (2.7 - 3.4m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 60.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 7 (3.8m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 43.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 7 (3.8m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 43.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 8 (4.3m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 58.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 8 (4.3m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 58.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 9 (5m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 47.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 9 (5m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 47.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 10 (5.8m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 52 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 10 (5.8m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 52 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 11 (6.2m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 30 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 11 (6.2m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 30 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP -

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 12 (6.8m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 52.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP

Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil JoreigeTrilogies, Monasteraki 12 (6.8m), 2018-2021Work on paper, photo, printed drawing and handwriting in blue pencil44 x 52.5 cm (framed)Edition 1 of 5 + 2AP

-